Translate this page into:

Trends in the publication of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Africa: A systematic review

*Corresponding author: Olakayode Olaolu Ogundoyin, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan and University College Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo, Nigeria. kayogundoyin@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ogundoyin OO, Ajao AE. Trends in the publication of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Africa: A systematic review. Ann Med Res Pract 2021;2:3

Abstract

There are still global variations in the epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, although the clinical presentations may be similar. Outcome of management, however, may depend on the degree of evolution of management of the anomaly. This review aimed at evaluating the trends of reporting of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis from Africa. An evaluation of all publications from Africa on infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis focusing on epidemiology, evolution of management of the anomaly was carried out. Literature search of all publications from Africa on Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis was conducted from January 1, 1951, to December 31, 2018. The articles were sourced from the databases of African Index Medicus, OvidSP, PubMed, African Journal Online, and Google Scholar. Extracted from these publications were information on the type of article, trend of reporting, the country of publication, demographic details of the patients, number of cases, clinical presentation, pre-operative management, type of surgical approach, and the outcome of management. Overall, 40 articles were published from 11 countries. Of these, 16 (40.0%) were published in the first 35 years (Group A, 1951–1985) and 24 (60.0%) published in the later 33 years (Group B, 1986– 2018). Case reports 8 (20.0%) and case series 5 (12.5%) were predominant in Group A, whereas retrospective studies 12 (30.0%) predominated in Group B. The countries of publication included Nigeria (27.5%), South Africa (15.0%), Egypt (12.5%), Tanzania (10.0%), and Zimbabwe (10.0%). A total of 811 patients diagnosed and managed for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) were reported. Their ages ranged from 1 day to 1 year with an incidence that ranged from 1 in 550 to 12.9 in 1000. There were 621 boys and 114 girls (M:F – 5.5:1). All the patients were breastfed with an average birth rank incidence of 42.4% among firstborns, 19.5% in second borns, 15.2% in third borns, 13.2% among fourth borns, and 10.0% among fifth borns and beyond. Associated congenital anomalies were reported in 5 (12.5%) studies with an incidence of 6.9–20% occurring in a total of 28 patients. All but 3 (7.5%) studies reported that open surgery was adopted to perform Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy on the patients. Reported post-operative complications include mucosal perforation in 8 (20.0%) studies, surgical site infection in 7 (17.5%), gastroduodenal tear 2 (5.0%), and hemorrhage and incisional hernia in 1 (2.5%) study each. Mortality was reported in 26 (65.0%) studies with a range of 1.8–50% and a mean mortality rate of 5.2%. There has been a change in the trend of reporting IHPS in Africa over the years, with increasing comparative studies on the modalities of management compared to case reports and series. Still very limited work has been done in the aspect of genetics and etiology of IHPS among Africans. There is a need to increase funding in this regard and to encourage multi-center collaborations in the study of this relatively rare condition.

Keywords

Africa

Hypertrophic

Infantile

Pyloric stenosis

INTRODUCTION

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) is an anomaly whose etiology is not clear, but there is global variation in its epidemiology. It is characterized by progressive hypertrophy of the circular muscles of the pylorus with consequent obstruction of the gastric outflow, mostly in neonates and infants under the age of 1 year.[1] The resulting gastric outlet obstruction produces a clinical manifestation of postprandial, projectile, non-bilious vomiting with associated palpable epigastric abdominal mass.[2-4] IHPS is highly prevalent in the Caucasian population with an incidence of 5/1000 newborns[5-7] in comparison to the African population in which it is rarer.[8] Other well-documented risk factors include a male preponderance (especially firstborn male) with a 4–5 times higher risk than females, young maternal age, and positive family history of IHPS.[5,6] Clinical diagnosis is usually made following a palpable mass in the epigastrium during feeding; however, this may sometimes be difficult to appreciate. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and contrast study of the upper gastrointestinal tract have proved very valuable in identifying the olive-shaped mass in the epigastrium.[1] Following adequate pre-operative resuscitation to correct fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, Ramstedt’s Pyloromyotomy[9] is often the surgical treatment of choice with a good post-operative outcome.

The relatively rare nature of this anomaly in the African population has made literatures from Africa to be very limited on the epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, management, and clinical outcome of IHPS. This systematic review sought to evaluate the trends of reporting IHPS from all publications emanating from various centers in Africa.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The guidelines provided by the 2009 statement of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis[10] were used to carry out a systematic review of all literatures on IHPS emanating from Africa within the last seven decades from January 1951 to December 2018. Searches were conducted of all articles in the databases of African Index Medicus, OvidSP, PubMed, and African Journal Online added with Google Scholar Search using “Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis” AND “Africa” OR “Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis” AND “Africa.” Full evaluation of each article was performed to identify those that reported IHPS in Africa. The relevance of these articles was examined and inclusion criteria were case reports, case series, and original articles. Excluded were review articles, commentaries, letters to the editor, and any other publication that did not provide adequate patients’ information. Articles that were published in languages other than English language were translated to English language using Google translator. Recorded from these publications were information on the type of article, trend of reporting, the country of publication, demographic details of the patients, number of cases, clinical presentation, pre-operative management, type of surgical approach, and the outcome of management. The trend of reporting was examined by comparing the publications in the first 35 years of the study (1951–1985) with the ones published in the following 33 years of the study (1986–2018). Analysis of data was performed using Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet 2010. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and proportions, while continuous variables were summarized using the mean.

RESULTS

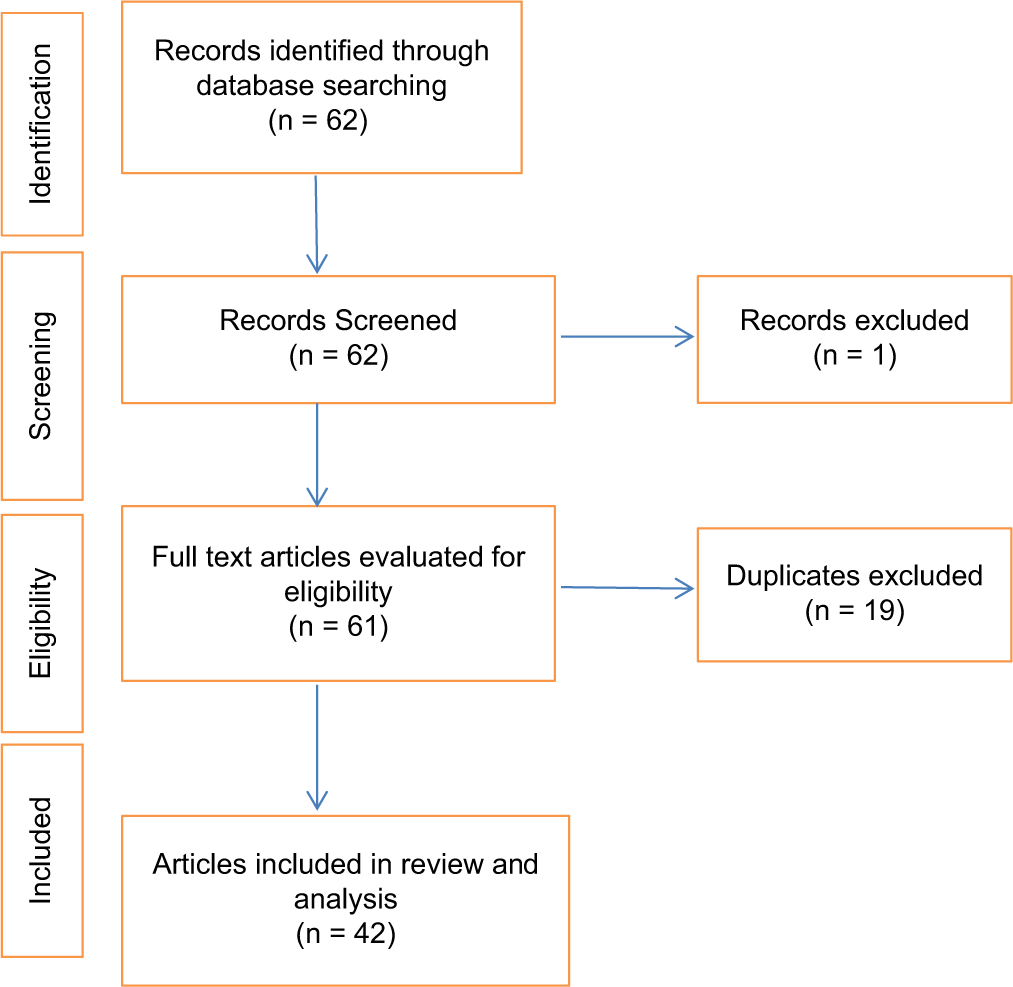

Following the database search for IHPS in Africa, a total of 62 publications were obtained with 59 publications meeting the criteria for the study after screening. A total of 40 articles were evaluated fully for the study after 19 duplicates were excluded [Figure 1]. Of these, 16 (40.0%) articles were published within the first three and a half decades of the study[11-26] [Table 1a] from 1951 to 1982 (Group A) and 24 (60.0%) were published in the last three and a half decades [Table 1b] from 1983 to 2018 (Group B).[9,27-49] There were 14 (35.0%) case reports,[12,14-17,19,21,24,32-34,43-45] of which eight (20.0%) were published within the first three and a half decades[12,14-17,19,21,24] and six (15.0%) articles were published later.[32-34,43-45] Seven (17.5%) articles were case series,[11,18,20,22,23,36,41] all but two (5.0%)[36,41] were published within the first three and a half decades, 15 (37.5%) articles were retrospective studies[9,13,25-31,35,37,39,40,46,48] with three (7.5%) published in the first three and a half decades[13,25,26] of the study, and 11 (27.5%) in the last three and a half decades.[9,27-31,35,37,39,40,46,48] There were four (10.0%) prospective studies,[38,42,47,49] all of which were published in the last three and a half decades of the study. Eleven (27.5%) articles emanated from Nigeria,[11,20,23,26,31,33-35,43,45,48] 6 (15.0%) from South Africa,[15,18,24,29,37,39] 5 (12.5%) from Egypt,[32,38,42,47,49] 4 (10.0%) each from Tanzania[9,17,28,44] and Zimbabwe,[12,13,21,22] 3 (7.5%) from Uganda,[14,16,19] 2 (5.0%) each from Cameroon,[41,46] and Ethiopia[27,40] whereas 1 (2.5%) each were published from Republic of Benin,[36] Ghana,[30] and Sudan.[25]

- Flowchart for article selection for the study.

| Authors | Year | Type | Country | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitcher | 1953 | Case Series | Nigeria | 2 |

| Marks | 1955 | Retrospective Study | Zimbabwe | 25 |

| Shepherd-Wilson and Gelfand | 1955 | Case Report | Zimbabwe | 1 |

| Griffiths | 1956 | Case Report | South Africa | 1 |

| Luder | 1956 | Case Report | Uganda | 1 |

| Hamilton | 1957 | Case Report | Uganda | 1 |

| Menezes and Thethravusamy | 1957 | Case Report | Tanzania | 1 |

| Scragg | 1958 | Case Series | South Africa | 3 |

| Boroda | 1960 | Case Report | Uganda | 1 |

| Swan | 1961 | Case Series | Nigeria | 10 |

| Grave | 1961 | Case Report | Zimbabwe | 1 |

| Hammar and Forbes | 1964 | Case Series | Zimbabwe | 3 |

| Audu | 1964 | Case Series | Nigeria | 5 |

| Javett et al. | 1973 | Case Report | South Africa | 1 |

| Hassan and Bayomi | 1975 | Retrospective Study | Sudan | 17 |

| Johnson and Adekunle | 1976 | Retrospective Study | Nigeria | 31 |

| Authors | Year | Type of study | Country | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemessa | 1990 | Retrospective Study | Ethiopia | 40 |

| Carneiro | 1991 | Retrospective Study | Tanzania | 15 |

| Emmink et al. | 1992 | Retrospective Study | South Africa | 62 |

| Tandoh and Hesse | 1992 | Retrospective Study | Ghana | 84 |

| Nmadu | 1992 | Retrospective Study | Nigeria | 20 |

| Gad et al. | 2003 | Case Report | Egypt | 1 |

| Okafor et al. | 2004 | Case Report | Nigeria | 1 |

| Egri-Okwaji et al. | 2005 | Case Report | Nigeria | 1 |

| Osifo and Evbuomwan | 2008 | Retrospective Study | Nigeria | 57 |

| Fiogbe et al. | 2009 | Case Series | Benin Republic | 2 |

| Banieghbal | 2009 | Retrospective Study | South Africa | 32 |

| Eltayeb and Othman | 2011 | Prospective Study | Egypt | 40 |

| Saula and Hadley | 2011 | Retrospective Study | South Africa | 63 |

| Tadesse and Gadisa | 2014 | Retrospective Study | Ethiopia | 55 |

| Tambo et al. | 2014 | Case Series | Cameroon | 2 |

| Chalya et al. | 2015 | Retrospective Study | Tanzania | 102 |

| Nofal et al. | 2016 | Prospective Study | Egypt | 20 |

| Ogunlesi et al. | 2016 | Case Report | Nigeria | 1 |

| Bizzocchi and Metz | 2016 | Case Report | Tanzania | 1 |

| Seyi-Olajide et al. | 2017 | Case Report | Nigeria | 1 |

| Ndongo et al. | 2018 | Retrospective Study | Cameroon | 21 |

| Elnaggar et al. | 2018 | Prospective Study | Egypt | 20 |

| Ezomike et al. | 2018 | Retrospective Study | Nigeria | 26 |

| Mohamed et al. | 2018 | Prospective Study | Egypt | 40 |

A total of 811 patients diagnosed and managed for IHPS were reported with an age range of 1 day–1 year and an incidence that ranged from 1 in 550 to 12.9 in 1000. Sex incidence was reported by 35 studies (87.5%) and there were 621 boys and 114 girls (M:F – 5.5:1). All the patients were breastfed and the average birth rank incidence was 42.4% among firstborn, 19.5% in second, 15.2% in third, 13.2% among fourth, and 10.0% among fifth born and beyond. Vomiting was the most common clinical presentation reported by 20 (50.0%) articles, this is followed by visible peristalsis 19 (47.5%) and palpable tumor reported by 17 (42.5%) articles. Twelve (30.0%) articles reported electrolyte problems, of these, only one article (2.5%) had normal serum electrolytes. The reported electrolyte derangements included hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis reported by 7 (17.5%) articles each, hypochloremia by 6 (15.0%), and hyponatremia by 5 (12.5%).

Associated congenital anomalies were reported in five (12.5%) studies, with an incidence of 6.9–20% occurring in a total of 28 patients. Inguinal hernias were the most common associated anomalies (11 patients) reported by all the studies. Others included congenital heart defects (5 patients), neural tube defects, undescended testis, Down’s syndrome, and craniosynostosis in 2 patients each, rectovaginal fistula, cleft palate, and Meckel’s diverticulum in one patient each. Thirty-five (87.5%) studies reported the operative procedures performed on the patients. Of these, all but three (7.1%) studies reported that open surgery was adopted to perform the pyloromyotomy. The remaining three studies reported laparoscopic pyloromyotomy using endo umbilical approach.[39,47,49] Of the open surgical approach, right upper transverse approach was most commonly used, other approaches included circumumbilical (3, 7.5%), supraumbilical (3, 7.5%), and upper midline (1, 2.5%). Mucosal perforation was reported by 8 (20.0%) studies with a range of 2.5–10.9%. Other post-operative complications reported included surgical site infection in 7 (17.5%) studies, gastroduodenal tear in 2 (5.0%), hemorrhage and incisional hernia in 1 (2.5%) study each.

Mortality was reported in 26 (65.0%) studies with a range of 1.8–50% and a mean mortality rate of 5.2%. The mean duration of hospital stay ranged from 2 to 13 days.

DISCUSSION

Trend of publications

A review of publications revealed a marked increase in the number of publications in the latter years, with the second group accounting for 60% of all publications used in this review. The increase is believed to result from increased awareness about the anomaly resulting in change of attitude of people across the continent about childhood surgical diseases and their treatment,[50] increasing number of specialist surgeons dedicated to the management of the surgical neonates and infants, as well as improvement in the diagnosis and treatment of the anomaly and changing trends in the attitude of reporting cases. Case reports and case series accounted for 52.5% of the publications, with majority these reports published in the first three and a half decades of the review. The relatively rare nature of this anomaly in Africans compared to Caucasians and Asians may account for this. Of the remaining 47.5%, a considerable proportion of the publications, especially the retrospective studies,[9,13,25-31,35,37,39,40,46,48] were dedicated to describing the pattern of presentation and outcome of management of the anomaly, whereas the prospective studies[38,42,47,49] tried to assess the outcome and usefulness of newer methods of managing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of IHPS varies from one region of the world to the other and from one ethnic/racial group to another. It is a disease that is very common in Caucasians but less common among Africans and Asians, with reported incidence that ranged from 0.39/1000 newborns among the Taiwanese in Asia.[1] to 5/1000 newborns among the Caucasians.[5-7,51,52] There is a similar variation in the reported incidence of IHPS in the publications from Africa which ranged from 1/5500 to 12.9/1000 children.[27,28,40] Of the three publications that reported the incidence of IHPS, the reported incidence of 1/5500 live births from Tanzania[28] is considerably lower than the observed trends in other parts of the world.[1,3,8,50,53-56] This further suggests that IHPS is relatively less prevalent in the African population.

Risk factors

The etiology of IHPS is unknown; however, many risk factors have been suggested. Studies have reported interaction between genetic and environmental factors in the etiology of IHPS.[56,57] Environmental risk factors include infant breastfeeding pattern,[58] Helicobacter pylori infection,[59] maternal smoking,[60] and exposure to drugs.[61-63] Other factors which may be genetic include positive family history, twins, and maternal age. Reports on the relationship of breastfeeding to the incidence of IHPS have shown an inverse relationship, with some studies reporting a decrease in incidence with increasing frequency of breastfeeding,[64,65] others reported increased incidence with a decrease in the frequency of breastfeeding.[66] An outlook on the breastfeeding practices in Africa revealed that over 95% of infants are breastfed exclusively.[67-69] In a study of the effect of exclusive breastfeeding on the incidence of IHPS in Nigeria, the incidence of IHPS fell steadily from the late 1980s to the early 1990s when exclusive breastfeeding was introduced in the country.[35] This supports the earlier reports that breastfeeding may have a protective effect on the development of IHPS and this may account for the relatively lower incidence of IHPS in the African population,[26,33,70] where breastfeeding is widely practiced. The reported cumulative gender incidence reported in African publications is similar to the reported incidence in the Caucasians and Asians with IHPS more predominant in boys than girls.[1,4,5,71,72] Since the first report that linked the birth rank to IHPS as a risk factor,[73] many series have also discovered that the risk is highest with firstborn infant and declines with increasing birth order;[53,58,66,74-75] an observation that was also reported by the publications from Africa.[9,13,23,27,28,30,39,40,46,48]

Associated congenital anomalies have not been commonly reported in patients with IHPS supporting the belief that IHPS is more likely an acquired condition.

Key aspects of the study

Although only one case report tried to identify the etiology of IHPS at the genetic level,[32] it will be interesting if the relatively rare incidence of IHPS in Africans compared to Caucasians and Asians could stimulate extensive research on the etiology of the disease in the African continent.

In high-income countries (HIC), management of IHPS evolved from medical management to surgical management. Initially, IHPS was treated medically using antispasmodics such as atropine and scopolamine, whereas surgical management was adopted for cases with failed medical management and complicated cases.[44] Surgical management is now the gold standard in the management of IHPS. It has also evolved from open surgery to more cosmetically acceptable laparoscopic surgery that allows for quick recovery and early discharge from the hospital. The continent has witnessed slow progress in the evolution of management of IHPS as some centers still report medical management of pyloric stenosis. This probably may result from a lack of trained personnel or inadequate facilities for the surgical management of the patients.[36,44] Open surgery with varying surgical approaches is still very common in the continent, especially sub-Saharan Africa where many centers cannot boast of availability of pediatric laparoscopic facilities with inadequate experience in laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. The proximity to Europe of the few centers[39,47,49] which published studies on laparoscopic pyloromyotomy may account for the recent reports on laparoscopic management from the continent.

The reported morbidity and mortality of IHPS from the continent are still very high compared to outcomes from HICs.[11,18,46,48] Late presentation, lack of requisite facilities for diagnosis, non-availability of appropriate intravenous fluid, and inadequate resuscitation may account for this.

Limitations of study

The publication of articles in journals that are not indexed a very common phenomenon in the continent which reduces the global visibility of these articles is a major limiting factor. Furthermore, articles that did not use the term “Africa” may have been inadvertently excluded from the search.

CONCLUSION

The studies indicate that there is a gradual departure of publications from descriptive studies to comparative studies on newer modality of management of IHPS after the awareness about IHPS had been established. There were no publications on the etiology of IHPS to evaluate the interplay of genetics and environmental factors in Africans. Therefore, adequate funding should be provided by stakeholders to intensify research in this area as it relates to Africans. There is also the need to introduce more recent methods of management and to assess the outcome of these in Africa. Emphasis should also be made to publish these articles in indexed journals for more visibility and accessibility.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Epidemiological features of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Taiwanese children: A nation-wide analysis of cases during 1997-2007. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19404.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in New York state 1983 to 1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:1123-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Greater Glasgow area, 1980-96. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:379-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent changes in the features of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:369-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decline in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Germany in 2000-2008. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e901-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: An association in twins? Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:383-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Epidemiology, genetics, and clinical update. Adv Paediatr. 2011;58:195-206.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1997;11:407-27.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis at a tertiary care hospital in Tanzania: A surgical experience with 102 patients over a 5-year period. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:690.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in two West African Children. West Afr Med J. 1953;2:210-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an African Infant. Cent Afr J Med. 1955;1:99-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the Africa. South Afr Med J. 1958;32:1053-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital pyloric stenosis in the African infant. Br Med J 1961:545-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a luvale child. Cent Afr J Med. 1961;7:449-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen's muscle and infantile hypertrophic pyloric. J Pediatr Surg. 1973;8:383-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Sudanese children. Environ Child Health. 1975;21:180-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1976;28:191-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertropic pyloric stenosis in a children's hospital a retrospective study. Ethiop Med J. 1990;28:169-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Dar Es Salaam. Cent Afr J Med. 1991;37:93-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a Third-World environment. South Afr Med J. 1992;82:168-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alterations in serum electrolytes in congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A study in Nigerian children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:169-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A novel point mutation of the androgen receptor (F804L) in an Egyptian newborn with complete androgen insensitivity associated with congenital glaucoma and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Clin Genet. 2003;63:59-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A case report. Trop J Med Res. 2004;8:60-3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Unusual presentation of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a ten-week old infant. Niger J Paediatr. 2005;32:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does exclusive breastfeeding confer protection against infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis? A 30-year experience in Benin city, Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr. 2008;55:132-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The medical treatment of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Cotonou (Benin): about two cases. Clin Mother Child Health. 2009;6:1025-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid correction of metabolic alkalosis in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with intravenous cimetidine: Preliminary results. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:269-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supraumbilical pyloromyotomy: A comparative study between intracavitary and extracavitary techniques. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:134-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the Third World. Trop Doct. 2011;41:204-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A retrospective study from a tertiary hospital in Ethiopia. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2014;19:120-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in infants: Is it a congenital or acquired disorder? Reflections on 2 cases. Springer Plus. 2014;3:555.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyloromyotomy for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis using a modification of the Tan and Bianchi circumumbilical approach. Ann Pediatr Surg. 2016;12:1-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with unusual presentations in Sagamu, Nigeria: A case report and review of the literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:114.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treating pyloric stenosis medically in a resource poor setting. Ann Pediatr Child Health. 2016;4:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and bilious vomiting: An unusual presentation. J Clin Sci. 2017;14:207-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A 4 year experience from two tertiary care centres in Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis using a myringotomy knife. Ann Pediatr Surg. 2018;14:60-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis our experience and challenges in a developing country. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2018;15:26-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modified Bianchi pyloromyotomy versus laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for patients with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Intraoperative considerations and parents' satisfaction. Ann Pediatr Surg. 2018;14:222-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Surgically correctable congenital anomalies: Prospective analysis of management problems and outcome in a developing country. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:126-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The changing epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Scotland. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:1007-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Texas, 1999-2002. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82:763-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a Danish population, 1950-84. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:413-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Sweden 1987-96. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:379-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trends in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950-1984. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1988;2:148-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A comparative study of incidence and other epidemiological characteristics in seven European regions. J Matern Fetal Neonat Med. 2008;21:599-604.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The continuing enigma of pyloric stenosis of infancy: A review. Epidemiol. 2006;17:195-201.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breast feeding and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Population based case-control study. Br Med J. 1996;312:745-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is Helicobacter pylori a cause of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis? Med Hypotheses. 2000;55:119-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal smoking and risk of hypertrophic infantile pyloric stenosis: 10-Year population based cohort study. Br Med J. 2002;325:1011-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after maternal postnatal use of macrolides. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:104-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and infant use of erythromycin and other macrolide antibiotics as risk factors for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr. 2001;139:380-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Very early exposure to erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:647-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The increasing incidence of infantile pyloric stenosis. Irish J Med Sci. 1993;162:175-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing incidence of infantile pyloric stenosis. Arch Dis Child 983;. ;58:582-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trends in pyloric stenosis incidence, Atlanta, 1968 to 1982. J Med Genet. 1987;24:482-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding: A study of two sub-districts in the Atwima Nwabiagya district of Ghana. The Pan Afr Med J 2015. ;. ;22:248.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breast-feeding in sub-Saharan Africa: outlook for 2000. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:929-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of infant-feeding patterns on early mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Durban, South Africa: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 1999;354:471-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A study of feeding practices and other possible causes. CMAJ. 1989;140:401-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis before 3 weeks of age in infants and preterm babies. Pediatr Int. 2011;53:18-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Has anything changed? J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:33-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Belfast, 1957-1969. Arch Dis Child. 1975;50:171-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyloric stenosis in the Oxford record linkage study area. J Med Genet. 1976;13:439-48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]