Translate this page into:

Trend of health worker’s strike at a Tertiary Health Institution in North Central Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Dalyop Davou Nyango, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Jos, Jos, Plateau, Nigeria. drnyango@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Nyango DD, Mutihir JT. Trend of health worker’s strike at a Tertiary Health Institution in North Central Nigeria. Ann Med Res Pract 2021;2:1.

Abstract

Objectives:

Workers’ strike is a global phenomenon since antiquity. In Nigeria, health-care sector has been rocked by series of strikes spanning variable periods with immeasurable losses. Ethical consideration and inter-professional rivalry are the main concern attracting much debate in the health sector. The objectives of the study were to determine the trend of health worker’s strike actions, the main agitators, and to make some recommendations.

Material and Methods:

This was a retrospective study of the labor ward records of the Jos University Teaching Hospital from January 1, 1985, to December 31, 2019, duration of 35 years. The data were collated and analyzed using simple percentages and the figures corrected to the nearest decimal point.

Results:

A total of 42 strike actions, about 2 strikes/year. The trend shows a multi-modal pattern, with the highest peak of 5 strikes in 2004 and 2013. There were cumulatively 58.5 months of strikes out of the 442 months of the period of study, giving a percentage of 13.2%. While doctors had more frequent strikes (52.3%), non-doctors under the umbrella of Joint Health Sector Union and nurse/midwives accounted for over half (58.1%) of the duration of the strikes. The resident doctors are the main agitators of doctors’ strike accounting for about half (45.2%) of the total health workers’ strikes, while NMA accounted for only 3 (9.4.%). Most strike actions occur at the end of the year, with spill into the first quarter of the following year.

Conclusion:

Health workers’ strike remains a perennial problem. Inter-professional rivalry is a major challenge in the health sector with far reaching implication without immediate government intervention. Addressing challenges in the residency training program will go a long way in reducing doctors’ unrest in the health sector.

Keywords

Strike actions

Industrial disputes

Withdrawal of services

Essential services

Jos

INTRODUCTION

Workers’ strike is a global phenomenon since antiquity. While medical strikes occur globally, the impact is more severe in developing countries with fragmented health-care system, poorer socio-economic circumstances, and lack of viable alternative means of obtaining healthcare. In Nigeria, health-care sector has been rocked by series of strikes spanning variable periods with immeasurable losses.[1-4] Workers’ strike or industrial action is defined as “…the collective withholding of labor/services by a category of professionals, for the purpose of extracting concessions or benefits, typically for the economic benefits of the strikers.[5] Workers’ strike by any group or unit will therefore have far reaching implication on the progress toward achieving universal health coverage (UHC).[6]

It is seen as an essential element in the principle of “collective bargaining,” as some have put it, “collective bargaining without the right to strike amounts to collective begging.”[7,8] Striking is generally the last resort to solving a problem and occurs when the collective bargaining process makes insufficient inroads and the unions are not satisfied with management’s offer to correct the situation. Strikes are considered a fundamental right and therefore an essential weapon in the armory of organized labor in democratic societies.[6,7] Some proponents say to deny any group of workers, including “essential workers” the right to strike is akin to enslavement.[9] National constitutions respect these right. Nigeria is a party to the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights establishing the right to strike.[6,7] The right to strike for the purposes of collective bargaining is one of the fundamental rights enshrined in Section 27 of The South African Constitution.[10] The right of workers’ strike is enshrined in most African country’s legal system with varying clauses.[11-13]

However, there has been much debate about whether it is ethical to withdraw services deemed essential for survival.[14-16] An essential service is a service in which it’s interruption endangers the life, personal safety or health of the whole or part of the population. Yet, several arguments support withdrawal of essential services. Some say strikes may be morally acceptable if directed toward improving workers’ conditions and their ability to care for future of patients,[17] still others support strikes if proportionate and properly communicated.[18,19] The ILO recognized the rights of workers to strike as a legitimate means of defending their occupational interest, but emphasized the importance of imposing restrictions for groups of workers in sensitive areas of the public service. Where strikes becomes inevitable, the ILO suggested that authorities should make available alternative procedures for processing grievances and disputes in areas of essential services.[20]

Although determinants of health workers’ strikes are diverse, studies revealed that the foremost reason for strikes in the medical field is poor working conditions, followed by wages, and other incentives for the workers.[21] Data on health workers’ strikes are sparse in low-income countries. This study aimed to determine the trend of health worker’s strike actions leading to withdrawal of services, the main agitators, and to make some recommendations.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study of the delivery register of Jos University Teaching Hospital from January 1, 1985, to December 31, 2019, a period of 35 years. The delivery register was retrieved from the record unit of the department of obstetrics and gynecology. Information about strike actions affecting delivery as documented in the register were extracted. The actual dates of the strike actions and other variables such as the number, duration, and the prosecutors of each strike action were also extracted. The data were collated and analyzed using simple percentages and the figures corrected to the nearest decimal point.

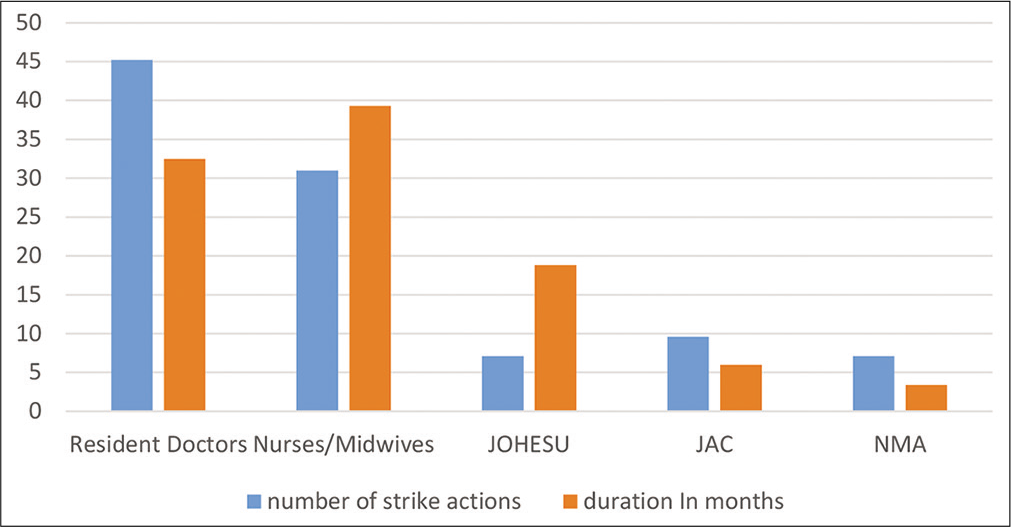

RESULTS

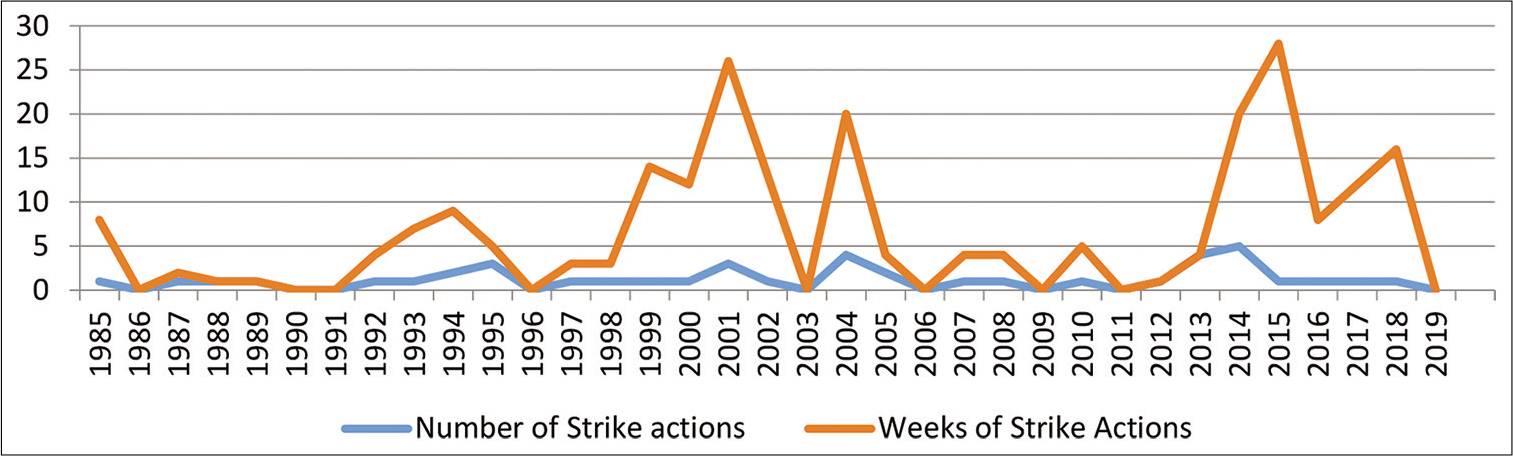

A total of 42 strike actions, about 2 strikes/year. The trend shows a multi-modal pattern, with the highest peak of 5 strikes in 2004 and 2013 [Figure 1]. There were cumulatively 58.5 months of strikes out of the 442 months of the period of study, giving a percentage of 13.2%. While doctors had more frequent strikes (52.3%), non-doctors under the umbrella of Joint Health Sector Union and nurse/midwives accounted for over half (58.1%) of the duration of the strikes [Figure 2]. The resident doctors are the main agitators of doctors’ strike accounting for about half (45. 2%) of the total period, while NMA accounted for only 3 (9.4.%) [Figure 3]. Most strike actions occur at the end of the year, with spill into the first quarter of the following year [Figure 4].

- Trend of strike actions by health workers.

- Distribution of strike action by professional bodies.

- Distribution of strike actions by Professional bodies.

- Distribution of Industrial Actions by months of the year.

Interestingly, the strike action by the whole health workers of the institution under the umbrella of JAC accounted for only a small fraction (6.9%) of the duration of strike actions. There were strike actions in all the months of the year [Figure 4]. The month of December seems to be the beginning of the peak of strike actions with spill into the first quarter of the following year [Figure 5].

- Quarterly distribution of strike actions.

DISCUSSION

This study identified the agitators and trend of workers’ strike in a tertiary institution. It shows that 13.2% of the working period was interrupted by worker’s strike. This agrees with the previous studies which show that workers’ strikes severely disrupt the provision of health-care services with significant social, political, organizational, and financial implications.[22,23] A significant finding in this study is that non-doctors accounted for over half (58.1%) of the duration of the strike suggesting an inter-professional rivalry [Figures 2]. This finding is in line with studies showing that struggle by different professional bodies to improve their social and political position within the society is a motivator for strike actions.[24] Another important finding in this study is the fact that resident doctors were the main agitators among doctors, accounting for 45.2% of the total period. This may suggest challenges with support for their training program not necessarily about compensation package. This agrees with findings which shows that strike actions are sometimes used to pressure governments to change policies that affect working conditions.[20,25] Furthermore, this may be related to findings from advanced capitalist societies including the United States which show a paradigm shift in the role of doctors from medical practice based on benevolent paternalism, to consumer rights and managed healthcare.[16]

The factors driving this change have been ascribed to “the complex corporate environment coupled with the stress of high malpractice rates, the struggle for reimbursement, administrative duties, and the general risks and burden of solo to small group practice.

In this study, we found that workers are more likely to have industrial disputes by the last quarter of the year, extending into the first quarter of the following year [Figure 5]. This is similar to the report from Kenya where strike actions in 2 consecutive years (2011 and 2012) both occurred in December with a spill into January the following year.[26] This may suggest that workers choose convenient periods to air their grievances. Therefore, in our study, we assumed that the weather contributed to the timing of the workers’ strike. This is because Jos is known for being extremely cold in the months of December extending into the early part of the following year. This is put forethought for couples intending to deliver in the hospital with more certainty, to plan their expected date of delivery outside this period. The strike action embarked on by the whole institution’s staff under JAC agrees with the previous reports that leadership/management and governmental inability to implement agreements were the common causes of healthcare workers’ strikes.[27] This goes to shows that management of health institution should improve their negotiation skills to reduce frequency of strikes as the impact of strikes can be devastating when they occur at periods of national or global health emergencies such as the Lassa fever, Ebola,[28] and the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

The strength of our study lies in the robustness of our data spanning over three decades with very instructive findings on the trend and agitators of health-care sector industrial actions. Such a robust data could serve as a point for further studies like the root causes of workers’ strike. However, being limited to one institution limit the generalization of these findings.

CONCLUSION

Health workers strike remains a perennial problem. Inter-professional rivalry is a major challenge in the health sector with far reaching implication without immediate government intervention. Addressing challenges in the residency training program will go a long way in reducing doctors’ unrest in the health sector.

Recommendation

Government and managers of health institutions should give residency training the attention it deserve, implement legitimate collective bargaining agreement and also promote inter-professional relationship will motivate healthcare workers and improve quality of health-care service delivery in tertiary institutions. The Federal Government should implement the Nigerian National Health Act which intends to positively impact UHC, access to and cost of healthcare, funding and insurance facilities, practice by health-care providers, quality and standards, patient care, and health outcomes. The Joint Learning Initiative on Human Resources for Health and Development, Report, in response to the demotivation of healthcare workers which moves them to strike action, states that “a key action is a significant upward revision of the total compensation package to a level that reflects the value placed on the work they do, is likely to discourage staff from wanting to leave public sector services.[29]

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Industrial action by healthcare workers in Nigeria in 2013-2015: An inquiry into causes, consequences and control-a cross-sectional descriptive study. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14:46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of disputes in the public service Southern African. J Ind Relat. 2008;50:578-94.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Suffer of Nigeria Health Care Workers Counting a Strike Who Cares? Nigeria Health Watch.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strikes by health workers: A look at the concept, ethics, and impacts. Am J Public Health. 1979;69:431-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of public sector health care workers strike: Nigeria experience. Rev Public Adm Manag. 2014;3:154-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Status of the Right to Strike in Nigeria: A Perspective from International and Comparative Law No. 15. RADIC 2007:54.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Human rights at work: Measuring the democratic rights of Nigerian workers by international standards. J Law Policy Global. 2015;35:125-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Section 23 (c) of the Labour Relations Act No.108 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. 1997. Available from: https://www.marxist.com/service-delivery-protests-strikes-south-africa.htm [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- 651 of the Ghanaian Law. 2003. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=66955&p_lang=en [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Section 110 (2) of the Labour Relations Act No. 4C of the Constitution of Malawi. 1996. Available from: https://www.iclg.com/practice-areas/employment-and-labour-laws-andregulations/malawi [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]

- [Google Scholar]

- Chapter 234 of the Laws of Kenya. 1996. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=28292&p_lang=en [Last accessed on 2019 Dec 09]

- [Google Scholar]

- Global medicine: Is it ethical or morally justifiable for doctors and other healthcare workers to go on strike? BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctors and strike action: Can this be morally justifiable? S Afr Fam Pract. 2009;51:306-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strikes by physicians: A historical perspective toward an ethical evaluation. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36:331-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A framework for assessing the ethics of doctors' strikes. J Med Ethics. 2016;42:698-700.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between job satisfaction and strike actions by health workers: A review of the literature. Web Pub J Bus Manag. 2014;2:12-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- 98 on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize and to Bargain Collectively.

- [Google Scholar]

- A strategy for industrial relations in Great Britain. Br J Ind Relat. 2002;10:12-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- What are the consequences when doctors strike? BMJ. 2015;351:h6231.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of an employees' strike on a community mental health center. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:188-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctors and the State: The Struggle for Professional Control in Zimbabwe Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 1999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of strikes by health workers on mortality between 2010 and 2016 in Kilifi, Kenya: A population-based cohort analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e961-7. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/lancetgh[Last accessed on 2019 May 22]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare workers' industrial action in Nigeria: A cross-sectional survey of Nigerian physicians. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16:54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebola virus disease epidemic in West Africa: Lessons learned and issues arising from West African countries. Clin Med (Lond). 2015;15:54-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Report of the Africa Working Group of the Joint Learning Initiative on Human Resources for Health and Development September 2006, The Health Workforce in Africa Challenges and Prospects. 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/hrh/documents/hrh_africa_jlireport.pdf [Last accessed on 2019 May 22]

- [Google Scholar]