Translate this page into:

Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and effects of service charges on notification among pregnant women attending antenatal care at General Hospital, Otukpo, Nigeria

*Corresponding author Joseph Anejo-Okopi, Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Health Sciences, Otukpo, Nigeria. josephokopi@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Anejo-Okopi J, Aju-Ameh CO, Agboola OO, Edegbene AO, Ujoh JA, Audu O, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and effects of service charges on notification among pregnant women attending antenatal care at General Hospital, Otukpo, Nigeria. Ann Med Res Pract 2023;4:1.

Abstract

Objectives:

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global public health problem, even though its prevalence is disproportionately high in resource-limited countries, it is still under-reported. Mother-to-child transmission is a major route of HBV transmission in an endemic region like sub-Saharan Africa. This study assessed the prevalence of HBV infection and the effect of service charge on hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) disease notification among pregnant women who attended the antenatal clinic at General Hospital, Otukpo, Benue State, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective cohort study with convenient sampling techniques were used for all pregnant women enrolled for antenatal care (ANC) within the reviewed period. Chi-square (χ2) test was used for the test of association between the independent variable and the main outcome of the study, with statistical significance set at P = 5%.

Results:

Of the total 1144 cases reviewed, 843 (73.7%) were tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and 301 (26.3%) were tested for HBsAg. The test for HIV was free while that of HBsAg was done out of pocket expenses. The majority of the women were between 25 and 30 years with a mean age of 25 ± 9.54 years. The seropositive rate for HIV was 2.4% (n = 20) while that of HBsAg was 5.6% (n = 17). The relationship between underreporting of positive and negative cases of HBsAg and service charges was statistically significant (P < 0.005).

Conclusion:

To achieve the global goal of elimination of HBV and, or reducing the prevalence of HBsAg in general population, the free opt-in screening just like in the case of HIV must be adopted for all pregnant women accessing ANC in public health facilities. This will inform both prevention, control, and antiviral management intervention strategies.

Keywords

Hepatitis B surface antigen

Pregnant women

Service charge

Otukpo

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a leading cause of death from viral hepatitis globally, accounting for about one million deaths annually,[1] and Africa is the worst hit due to the dwindling nature of the healthcare delivery service in the region. It has been reported that in Sub-Saharan Africa, the overall hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carrier rate in the general population is 5–20%, which is among the highest in the world. It has been reported earlier that Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is more likely in individuals who contracted the HBV infection perinatally than those through horizontal transmission; therefore, interrupting this mother-to-child transmission will significantly reduce the burden of liver disease.[2] The infection in pregnancy poses a serious risk to the neonate.[3] Despite the availability of effective childhood vaccines, the prevalence of HBV infection in sub-Saharan Africa remains unacceptably high. Without appropriate prophylaxis and post-exposure immune prophylaxis, infants born to HBV-infected mothers stand the risk of acquiring the virus which will eventually become chronic, and subsequently lead to death occasioned by the high transmission rate.[4]

Transmission of HBV from mother to child remains the silent driver of HBV infection rate most especially in developing countries, where the early detection of the virus is vital to prevention strategy. The prevention of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) is a key component to reduce the global burden of HBV since it is responsible for approximately one-half of chronic infections worldwide.[4] Hence, vaccination will reduce the risk of infection, as the risk of neonates acquiring the infection is as high as 90% in the absence of vaccination.[4] On the other hand, HBV infection in pregnancy is similar to that in the general population, though the infection is not teratogenic. However, infection associated with high viral load increases transmission and low birth weight and prematurity.[5] The screening of pregnant women and vaccination of infants have significantly reduced transmission rates.[6]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all infants receive three doses of vaccine that will provide a protection level of 95% ot more against HBV infection. The first dose is given 24 h after delivery, and a follow-up of additional two doses.[7] The use of vaccines at birth remains the hallmark of HBV prevention. In resource-limited countries including Nigeria, healthcare facilities are not easily accessible and potent vaccines are most times unavailable, and this accounts for the death of over 10 million children every year.[8]

Reports have shown that passive and active post-exposure prophylaxis using hepatitis B Immunoglobulin and hepatitis B vaccine accounts for 85–95% effectiveness in the prevention of vertical transmission.[9] About 13.0% of infants born to infected mothers with high HBV viral load are positive.[10] Earlier findings have shown that HBV vaccine failure is associated with an infant born to HBV-positive mothers.[11,12] Several interventional measures such as tenofovir prophylaxis at the third trimester, and child vaccination with both immunoglobulin and antigen within 24 h of birth have demonstrated some significant success rates.[13] The routine dose of the hepatitis B vaccine given to infants whose mothers tested positive with HBV a week after delivery may not be adequate to protect exposed babies from being infected.

Earlier studies have reported the prevalence of HBV among various sub-populations worldwide with heterogeneous estimates.[11,14,15] The prevalence of HBsAg among antenatal women varies significantly in African countries and ranges from 6% to 25%.[15-19] For instance, an earlier study reported a prevalence of 9.5% in Nigeria,[16] and the highest HBV prevalence was in rural settings (10.7%), with North West region having the highest (12.1%). Furthermore, the national survey of HBV showed a 12.2% prevalence in the general population.[20] The prevalence of HBsAg among pregnant women in Makurdi was 11.0%,[14] and 1.7%.[21] Despite these studies on the prevalence of HBsAg among women attending the antennal clinic, there is still a dearth of reliable data on the prevalence of HBV infection among mothers attending antenatal clinics at Secondary Facilities in Benue state, Nigeria. Therefore, the present study was aimed at determining the prevalence of HBV infection and the impact of service charges on the uptake of screening among pregnant mothers attending the Antenatal Clinic at Otukpo, Benue State Nigeria. The study forms part of the HBV baseline prevalence data of Benue South Senatorial District (BSSD) of Benue.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This retrospective study analyzed records of the antenatal care (ANC) registry from January to September 2021 at General Hospital Otukpo, Benue State, Nigeria. BSSD comprises nine local government areas, namely, Ado, Agatu, Apa, Obi, Ogbadibo, Okpokwu, Ohimini, Oju, and Otukpo with an estimated total population of 1,310,647. This research was carried out in Otukpo, the traditional headquarters of Benue Southern parts. It is located on 70 131N and 809 1E, 70 211N, and 80151E. It has an estimated landmass of about 390 sq. km and with an estimated population of 266,411 (2006, Census). The pregnant women who attended ANC from January to September 2021 were counseled for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HBV testing. The Otukpo General Hospital that has been seeded to the Federal University of Health Sciences Otukpo as the University Teaching Hospital. Some of the data captured from the records obtained are age, gender, education, occupation, HBsAg, and HIV status, and those without this information were excluded from the study. The pre-testing counseling was done in groups, while the post-testing counseling was done individually. Blood drawn from each pregnant woman was tested for serum HBsAg using an immunochromatographic rapid point-of-care test according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Diasorin, Italy). The test for HIV was free while that of HBsAg was done out of pocket expenses. The study received ethical approval from the Benue State Ministry of Health and permission from the Chief Medical Superintendent.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using the Statistical Program for the Social Sciences version 22. Chi-square (χ2) at a significant level of P < 0.05 and confidence level of 95% was used to determine the significance between associated factors (Age, education, and occupation) and prevalence of HIV and HBsAg.

RESULTS

A total of 1144 cases of pregnant women attending ANC at General Hospital, Otukpo, and Benue State, Nigeria were reviewed between January and September 2021. Of the 1144 cases reviewed, 843 (73.7%) were tested for HIV, while 301 (26.3%) were tested for HBsAg with all the months having patients presented for either HBsAg or HIV testing [Table 1].

| Variables | HIV | HBV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +ve | −ve | P-value | +ve | −ve | P-value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <25 yrs | 3 (0.38) | 91 (10.80) | >0.020 | 6 (1.95) | 60 (20.02) | 0.170 |

| >25 yrs | 17 (2.02) | 732 (86.80) | 11 (3.65) | 224 (74.38) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| <Primary | 5 (0.59) | 256 (30.37) | 0.560 | 5 (1.66) | 156 (51.83) | 0.040 |

| >Primary | 15 (1.78) | 567 (67.26) | 12 (3.99) | 128 (42.53) | ||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Employed | 8 (0.94) | 531 (63.00) | 0.190 | 14 (4.65) | 289 (96.01) | 0.010 |

| Unemployed | 12 (1.42) | 292 (34.64) | 3 (1.00) | 12 (3.99) | ||

HBV: Hepatitis B virus, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus

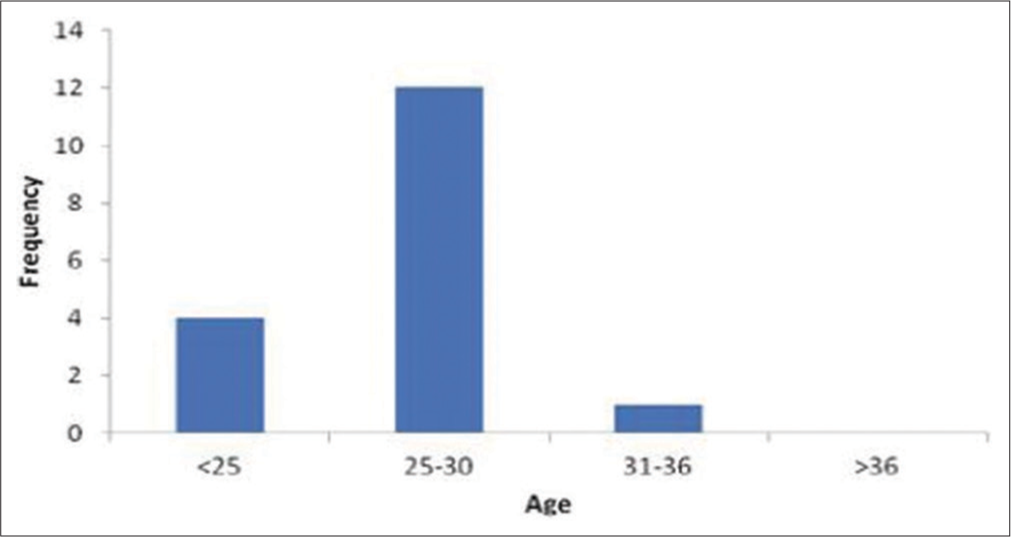

Overall, 5.65% and 2.37% tested positive for HBsAg and HIV [Figure 1 and Table 2], those older than 25 years had the highest prevalence of 3.65% and 2.02% for HBsAg and HIV, respectively [Figure 2]. There was no statistically significant difference between the proportions of HBsAg positives with respect to age, but there was a significant association between the screening result of the HIV and HBsAg tested among the pregnant women (P = 0.0001). Furthermore, the relationship between underreporting of positive and negative cases of HBsAg and service charges was statistically significant (P = 0.010). Among the pregnant women tested for HBsAg, the mean age was 25 ± 9.54 years with a median age of 27 years and a range between 21 and 36 years [Figure 2]. In terms of educational status, the prevalence of HBsAg was higher among pregnant women with higher educational status of > primary level (4.0%), while the those < primary level was 1.06%, for occupational status, majority 265/301 (88.0%) of the pregnant women tested positive to HBsAg were self-employed, with seropositivity of 14 (4.65%), while the unemployed was 1.00%; this result suggests that acquisition of HBV infection might have been influenced by higher education and employment status, with P = 0.040, and 0.010, respectively [Table1].

| Variables | Number | Positive n(%) | Negative n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | 301 | 17 (5.6) | 284 (94.4) |

| HIV | 843 | 20 (2.4) | 823 (97.6) |

| Total | 1144 | 37 (3.2) | 1107 (96.8) |

HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus

- Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen among pregnant positive attending antenatal care, General Hospital, Otukpo.

- Distribution of hepatitis B surface antigen in relation to age among pregnant women attending antenatal care, General Hospital, Otukpo.

The month of January had the highest number of patients 63/301 (21.0%)) tested for HBV, while September had the least number of patients 5/301 (1.6%) tested for HBV [Figure 3]. Although the number of patients who tested to be positive varies across the months, the months of January, May, and July had the highest number of seropositive patients. The seropositive rate of patients for HBV ranged from 0% to 6.3% with the month of January having the highest seropositivity rate within the study period.

- Distribution of the number of tested and positive hepatitis B surface antigen among pregnant women attending antenatal care, General Hospital, Otukpo.

The relationship between factors associated with HIV among women attending ANC in Otukpo general hospital was analyzed for factors such as age, educational status, and employment status. The χ2 test of independence showed that there was no significant association between age (P = 0.170), but there was a statistically significant relationship between employment status (P = 0.010) and educational status (P = 0.040) with HBsAg status [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

The major route of transmission of chronic hepatitis B infection is vertical transmission (mother-to-child) as well as horizontal early childhood transmission. Therefore, the prevention of these infections from the vertical or horizontal transmission is the most important strategy to control the HBV epidemic. Vertical transmission of HBV is more common in children born to women who have high HBV viral load in their blood at birth.

This study showed that the prevalence of HBV among pregnant women was 5.6%. Our finding is lower than an earlier study done in Jos North central Nigeria (7.4%), Makurdi 11.0%,[14] western Niger 9.5%.[16] Keffi 19.8%,[22] Gambia 9.20%,[11] and Iran 2.1% 9,[23] but similar to the reports from studies done in Ethiopia (5.9%)[24] and Northern Tanzania (5.7%).[25] The number of patients or pregnant women (as the case may be) tested for HBsAg was relatively higher than those tested for HIV in the present study. This may be occasioned by the availability of free screening exercises in most Government Hospitals in Nigeria as against the pocket expenses on the side of the patients for the diagnostic test for HBsAg.

The difference in this study might be due to many factors such as socioeconomic, sociocultural, and sexual practices including the study setting. Furthermore, the variations could be due to the small sample size done in a single health center. The prevalence of HBV infection is within the intermediate endemicity’ category by the WHO of 2–8%,[26] However, the prevalence is higher than in earlier studies from other African Countries such as Uganda (2.9%), Kenya (3.8%), and Ethiopia (3.5%), respectively.[27-29] The reason for this prevalence is not clear but could be due to a lack of access to universal testing of all pregnant women for hepatitis B. This suggests the need for urgent implementation and support of a national program for universal testing of hepatitis B in an intermediate and high endemic regions.

Regarding the sociodemographic factors, there was a significant association between the prevalence of HBsAg and educational (P = 0.040) employment status (P = 0.010) in this study. This might be due to the influence of economic empowerment that is directly proportional to higher education and employment status. This may also account for a casual sexual lifestyle that drives the transmission of HBV infection in regions, where multiple sexual partners and promiscuity are high. The significant associations between these factors (educational and occupational status) showed that women need to take necessary preventive measures to avoid acquiring HBV infection through the constant use of condoms and avoiding multiple sexual partners. Furthermore, an earlier study from Uganda showed that women with no stable partner have higher chances of acquiring HBV infection than those with a single partner.[27]

In some previous studies, age is significantly associated with HBV infection,[14,30,31] but this is in contrast to our finding, and similar to earlier studies in Nigeria and Uganda[27,32] that did not have a statistical significance association.

At present, our country’s hepatitis program does not carry out routine screening for HBV infection as part of standard care for women attending antenatal clinics, also, HBV vaccination for women who test negative for HBsAg, and there is neither no intervention through antiviral or HBV vaccination for the prevention of MTCT of HBV. The WHO recommends the use of tenofovir as prophylaxis for those who are positive for HBsAg for 4 weeks before delivery to reduce viremia and prevent transmission to neonates.

This suggests the urgent need for interventional measures to prevent HBV infection for women of reproductive age that will reduce perinatal HBV transmission with significant impact in endemic regions such as Nigeria. The use of universal coverage for HBV vaccination in pregnancy, antiviral prophylaxis, HBV immunoglobulin for HBV-exposed babies, and HBV vaccination of newborns could significantly reduce HBV transmission.[7]

Our finding provides baseline data and epidemiological information on the burden of HBV infection among pregnant women which could be used to advocate for making the evidence-based case for the scale-up of free HBV screening to women of reproductive age just like HIV and Syphilis in Nigeria.

Limitations of this study include a single-site retrospective nature of the study at a short period and a small study size with a lot of missing data. Furthermore, the use of the HBsAg rapid test without confirmation another DNA assay posed a challenge to true positivity. The authors were unable to confirm reports of prior HBV vaccination.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of HBV infection was intermediary in accordance with the WHO classification but could be more than the reported prevalence if testing is made free for all pregnant women as part of ANC. The study revealed that factors such as age had no statistically significant difference. However, there was a significant statistical association between the screening result of the HIV and HBsAg tested among pregnant women and the relationship between the under-reporting of positive cases and service charges. Furthermore, education and employment status were associated with increased chances of being hepatitis B positive. To reduce the burden of HBV infection: integration of HBV prevention services such as the use of antiviral prophylaxis, regular HBV vaccination, and use of HBV immunoglobulin is vital to the transmission prevention efforts. Further prospective studies involving pregnant women with HBV infection till delivery and after delivery are required, and the urgent need to test babies born to HBV-positive mothers to determine infant infection would be useful. This data will help inform the prevention, control, antiviral management, and elimination strategies to curb the HBV epidemic in Nigeria.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the State hospital management board, the General hospital management and the staff of the antenatal clinic for all their support.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declared no conflicts of interest exist.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Global Hepatitis Report 2017. 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-hepatitis-report-2017 [Last accessed on 2022 Jun 02]

- [Google Scholar]

- The association between maternal hepatitis B e antigen status, as a proxy for perinatal transmission, and the risk of hepatitis B e Antigenaemia in Gambian children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:532.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B and pregnancy: An underestimated issue. Liver Int. 2009;29:133-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2002 Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus: Guidelines on Antiviral Prophylaxis in Pregnancy. 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-000270-8 [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 02]

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review with meta-analysis: The risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1005-17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of infants born to women infected with hepatitis B. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1141-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices for use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:455-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arresting vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus (AVERT-HBV) in pregnant women and their neonates in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A feasibility study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e1600-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transplacental transfer of hepatitis B neutralizing antibody during pregnancy in an animal model: Implications for newborn and maternal health hepatitis research and treatment. Hepat Res Treat. 2014;2014:159206.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B virus sero-prevalence amongst pregnant women in the Gambia. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:259.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20 years into the Gambia hepatitis intervention study: Evaluation of protective effectiveness against liver Cancer assessment of initial hypotheses and prospects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3216-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenofovir alafenamide for prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation and de novo hepatitis. JGH Open. 2021;5:1085-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection among pregnant women in Makurdi, Nigeria. Afr J Biomed Res. 2008;11:155-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Jos, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2020;19:176-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B virus infection in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis of data published between 2010 and 2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1120.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus co-infection among HIV-1-positive patients in North-Central Nigeria: The urgent need for surveillance. Afr J Lab Med. 2019;8:622.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: New estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for over 20 age groups in 1999 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095-128.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of hepatitis B infection in Nigeria: A national survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:902-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B virus infection in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis of data published between 2010 and 2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1120.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care in central Nigeria. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2019;5:68.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2016;9:e3703.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis B virus among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at Mizan-Tepi university teaching hospital and Mizan health center, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:195-200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for Hepatitis B transmission in South Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112:544-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B virus burden in developing countries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11941.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Mulago Hospital, Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e033043.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, awareness and risk factors associated with hepatitis B infection among pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic at Mbagathi district hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:315.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus surface antigen and factors associated among pregnant women in Dawuro zone, SNNPR, Southwest Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:418.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, infectivity and correlates of hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in a rural district of the far North region of Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:454.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care: A cross sectional study in two hospitals in northern Uganda. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005889.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveying infections among pregnant women in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2:203-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]