Translate this page into:

Neonatal morbidity and mortality: A 5-year analysis at federal medical centre, Gusau, Zamfara State, Northwest Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Sunday O. Onazi, Department of Pediatrics, Federal Medical Centre, Gusau, Zamfara State, Nigeria. drsundayo@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Onazi SO, Akeredolu FD, Yakubu M, Jiya MN, Hano IJ. Neonatal morbidity and mortality: A 5-year analysis at federal medical centre, Gusau, Zamfara State, Northwest Nigeria. Ann Med Res Pract 2021;2:10.

Abstract

Objectives:

Neonatal morbidity and mortality have remained embarrassingly high in Nigeria compared to some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nigeria ranked first in the burden of neonatal deaths in Africa. Therefore, there is need to know causes of newborn diseases and deaths in our neonatal unit. The objective of the study was to describe the morbidity and mortality of newborns admitted into Special Care Baby Unit of Federal Medical Centre, Gusau, Nigeria over a 5-year period.

Material and Methods:

This is a retrospective study covering January 2012 to December 2016. The case folders of all newborns admitted during this period were retrieved and the following information were extracted: Sex of babies, diagnoses, outcome in terms of discharges, deaths, referrals, and discharge against medical advice (DAMA).

Results:

A total of 3,553 neonates were admitted during the period under review. The sex ratio for males and females was 1.4:1, respectively. The major diagnoses were neonatal sepsis (NNS) 36.5%, birth asphyxia 25.6%, and prematurity 16.1%. Mortality rate was 6.6% with major contributions from birth asphyxia (35.6%), prematurity (28.1%), and NNS (12.0%). DAMA rate was 1.7%.

Conclusion:

This study has shown that NNS, birth asphyxia, and prematurity are the dominant causes of morbidity and mortality. These are largely preventable.

Keywords

Neonatal

Morbidity

Mortality

Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

The survival rate of newborns correlates positively with high standard of obstetric care, neonatal care, and high socioeconomic development of nations. Neonatal mortality in Nigeria is second to India globally and the highest in sub-Saharan Africa.[1,2]

Neonatal mortality is still a significant public health problem in Nigeria as it accounts for 30% of the under-five mortality rate in Nigeria.[3]

There has been steady decline in neonatal mortality rate (NMR) worldwide and even in subSaharan African countries like Ghana and Uganda. However, such cannot be said of Nigeria as the decline is very minimal. Nigeria had a NMR of 40/1,000 live births in 2008 and it only declined to 36/1,000 live births in 2018.[4-6] There is need therefore to accelerate progress to reach the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of NMR of 12/1000 live births in 2030.[7]

The study was, therefore, conducted to describe the morbidity, mortality and outcome of babies admitted into the Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU) of Federal Medical Centre, Gusau, Nigeria.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A 5-year retrospective analysis of all the newborns admitted into the SCBU from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2016. The SCBU has two units, the in-born unit and the out-born unit. In both units, there are 19 baby cots, 11 incubators, nine phototherapy units, and one ventilator.

The SCBU serves newborn babies in Zamfara State, neighboring Sokoto, and Katsina States. The case folders of all the newborns admitted into SCBU during the 5-year period were retrieved. The following information were extracted from each folder: sex of babies, diagnoses, outcome in terms of discharges, deaths, referrals, and discharge against medical advice (DAMA). The data were entered into SPSS version 23 (IBM Armonk NY, USA) and analyzed. The result was presented in frequency tables and figures.

Ethical approval was obtained from FMC Gusau Ethical Committee before commencement of the study.

RESULTS

A total of 3553 neonates were admitted and managed in SCBU during the period under review with 2073 (58%) being males while 1480 (42%) were females, giving a male to female ratio of 1.4:1. Neonatal sepsis (NNS) was the most common disease of the newborn while the least frequent disease in this study was neonatal burns. This is shown in Table 1.

| S. NO. | Disease | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Neonatal Sepsis | 1,298 | 36.53 |

| 2. | Birth Asphyxia | 912 | 25.67 |

| 3. | Prematurity | 572 | 16.10 |

| 4. | Neonatal Jaundice | 418 | 11.77 |

| 5. | Congenital Malformation | 84 | 02.36 |

| 6. | Macrosomia | 80 | 02.25 |

| 7. | Meconium Aspiration Syndrome | 64 | 01.80 |

| 8. | Neonatal Meningitis | 38 | 01.07 |

| 9. | Neonatal Tetanus | 22 | 0.62 |

| 10. | Birth Trauma | 17 | 0.48 |

| 11. | Necrotizing Fasciitis | 13 | 0.36 |

| 12. | Hemorrhage | 09 | 0.25 |

| 13. | Respiratory Distress Syndrome | 09 | 0.25 |

| 14 | Neonatal Malaria | 08 | 0.23 |

| 15 | Failure to Thrive | 04 | 0.12 |

| 16 | HIV-exposed Infant | 03 | 0.08 |

| 17 | Neonatal Burns | 02 | 0.06 |

| Total | 3,553 | 100 |

A total of 3221 (91%) of neonates that were admitted were successfully managed and discharged home. The distribution of cases discharged is as shown in Table 2.

| S. No. | Cases | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Neonatal Sepsis | 1,251 | 38.93 |

| 2. | Birth Asphyxia | 811 | 25.18 |

| 3. | Prematurity | 477 | 14.80 |

| 4. | Neonatal Jaundice | 408 | 12.67 |

| 5. | Congenital Malformation | 80 | 2.50 |

| 6. | Macrosomia | 50 | 1.55 |

| 7. | Meconium Aspiration Syndrome | 42 | 1.30 |

| 8. | Neonatal Meningitis | 26 | 0.82 |

| 9. | Neonatal Tetanus | 16 | 0.50 |

| 10. | Birth Trauma | 16 | 0.50 |

| 11. | Necrotizing Fasciitis | 11 | 0.34 |

| 12. | Haemorrhage | 09 | 0.27 |

| 13. | Respiratory Distress Syndrome | 08 | 0.25 |

| 14 | Neonatal Malaria | 06 | 0.18 |

| 15 | Failure to Thrive | 03 | 0.09 |

| 16 | HIV-exposed Infant | 02 | 0.06 |

| 17 | Neonatal Burns | 02 | 0.06 |

| Total | 3,221 | 100 |

A total of 236 out of 3553 neonates managed during the period under review died, this brings the mortality rate to 6.6%. The distribution of the mortality by disease is shown in Table 3.

| S. No. | Disease | Number of deaths | Percentage | Case fatality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Birth Asphyxia | 84 | 35.6 | 9.2 |

| 2. | Prematurity | 68 | 28.14 | 11.9 |

| 3. | Neonatal Sepsis | 28 | 12.0 | 2.2 |

| 4. | Congenital Malformation | 15 | 6.50 | 7.9 |

| 5. | Meconium Aspiration Syndrome | 14 | 6.00 | 21.8 |

| 6. | Neonatal Meningitis | 10 | 4.24 | 26.3 |

| 7. | Neonatal Tetanus | 06 | 2.7 | 27.3 |

| 8. | Neonatal Jaundice | 05 | 2.12 | 1.2 |

| 9. | Neonatal Malaria | 02 | 0.9 | 25 |

| 10. | Birth Trauma | 01 | 0.45 | 5.8 |

| 11. | Haemorrhage | 01 | 0.45 | 11.1 |

| 12. | Failure to Thrive | 01 | 0.45 | 25 |

| 13. | Necrotizing Fasciitis | 01 | 0.45 | 7.7 |

| Total | 236 | 100 | - |

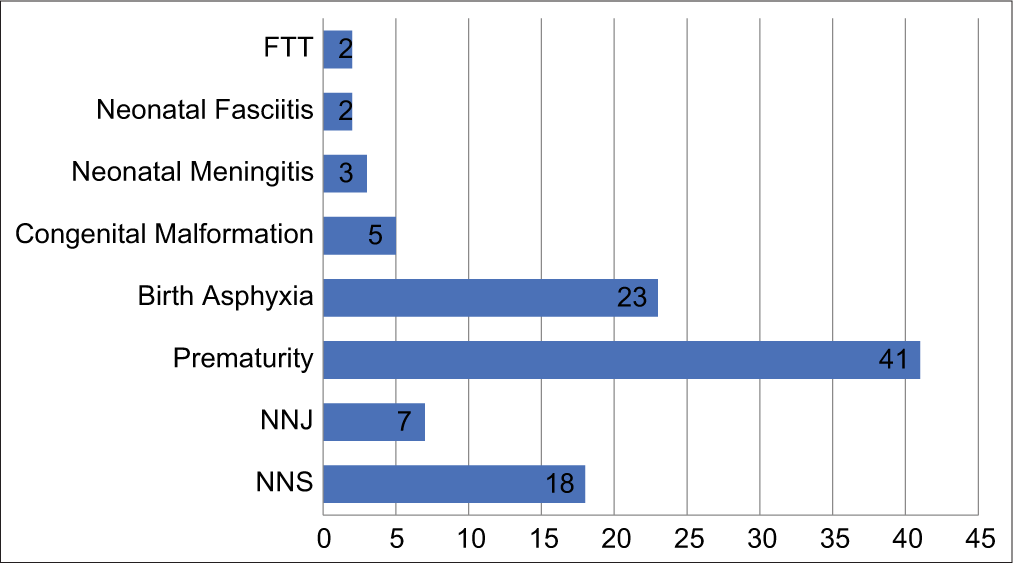

Out of the total 3553 neonates managed, 61 (1.7%) of them were DAMA. The distribution of DAMA by diseases is shown in Figure 1.

- Distribution of discharge against medical advice by disease. FTT: Failure to Thrive, NNJ: Neonatal Jaundice, NNS: Neonatal sepsis

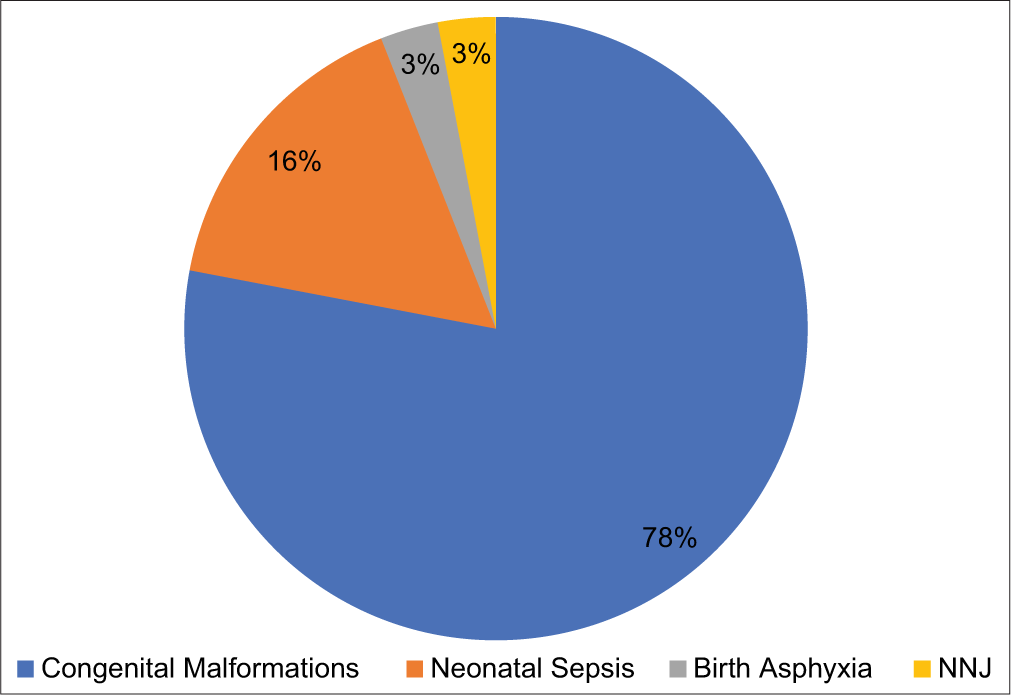

The neonates that were referred out for further management were 31 (0.9%) of the 3553 that were managed in the unit. Congenital malformations were the highest cases referred out. The distribution of cases referred out is as depicted in Figure 2.

- Distribution of referred cases by disease. NNJ: Neonatal Jaundice

DISCUSSION

The study recorded male’s preponderance over females. This finding is similar to what were reported by Ekwochi, et al. in Enugu,[7] also and Gwarzo in Dutse[8] and Garba et al. in Specialist Hospital, Gusau.[9] However, our findings were different from what were reported from Kano[10] and Lagos.[11] The reasons for the male preponderance may be due to cultural preference for male children as such increase tendency to bring them to hospital when they are sick.

Another reason is the genetic make-up of the male child which makes him more vulnerable to stress of diseases.

The most common disease of the newborn in this study is NNS and this is in agreement with studies from other parts of Nigeria[8,12-14] and Sudan.[15] This is in contrast to reports from Enugu and Kano where the most frequent disease in their studies was birth asphyxia.[7,10] The reason for the high cases of NNS may be due to high rate of home deliveries, poor cord care practices, and for the fact that the study period predates the wide scale-up of 4% chlorhexidine gel use in Nigeria. The least common disease is neonatal burns which were due to accidental fall into hot water. Neonatal accidents are rare in Nigeria.

The NMR in this study is 6.6%. This is comparable to the 7.16% reported from Birnin-Kudu, Jigawa State, Nigeria.[16] However, higher rate of 20.4% from State Specialist Hospital, Gusau,[9] 14.8% from Zaria,[17] 13.3% from Abuja, and 20.3% from Benin City.[18] The wide difference in mortality rates may result from few specialists available at the State Specialist Hospital and generally limited equipment for the care of newborns across the country as some of the publications were done more than a decade ago. The leading cause of death is birth asphyxia which is in consonant with findings from other parts of Nigeria.[7,19-21]

However, the findings from Azare[13] and Sagamu[22] revealed that prematurity were the leading cause of death in their centers. The three leading causes of death in this study were Birth Asphyxia, Prematurity, and NNS. This correlates with the reports from Dutse, Jigawa State,[8] and Benin City.[23] These causes of death are to a large extent preventable with effective health education, antenatal care, and delivery in hospital by our pregnant mothers under the supervision of skilled health attendants.

DAMA rate was 1.7%. This is lower than 5.2% reported from Azare[13] and 4.3% from Port Harcourt.[24] The rate of DAMA in this study is however higher than 0.4% obtained in Dutse.[8] Prematurity accounted for the highest number of cases of DAMA. The reason for this is because premature babies stay long in the hospital, the use of incubators and oxygen for their treatment adds to the high financial burden on care givers.

The highest number of neonates referred out of the unit was those diagnosed with congenital malformations. This was because we lacked resident consultant pediatric surgeon in the center.

CONCLUSION

The major causes of morbidity and mortality in this study are preventable. There is need to improve health education at community level for pregnant women to enhance their utilization of antenatal facilities, delivery in the hospital and infection prevention measures. The National Health Insurance Scheme should cover newborn health services. These measures when implemented, will give Nigeria a leap in the race towards attaining SDG by the year 2030.

Acknowledgment

The Medical Officers in the department, the health information management staff who retrieved the case folders and Dr. Chris Onwugamba are well acknowledged for their various roles in preparing this publication.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO Neonatal Mortality. 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://www.who.int.neonatal [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Group Child Mortality Estimation (IGME): Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int.maternal-child-adolescent/documents/level-trends-child-mortality-2012pdf [Last accessed on 2020 Sep 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Nigerian National Demographic and Health Survey. 2018. Available from: http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr359 [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Neonatal Mortality-UNICEF Data. 2020. Available from: https://www.unicef.org>media>file [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Demographics Health and Infant Mortality-UNICEF Data. 2020. Available from: https://www.unicef.org>country>nga [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Neonatal mortality: Risk factors and causes: A prospective population based cohort study in Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;8:130-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of morbidity and mortality of newborns admitted into the sick and special care baby unit of Enugu State University teaching hospital, Enugu state. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:346-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of morbidity and mortality among neonates seen in a tertiary hospital. Sahel Med J. 2020;23:47-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A study of neonatal mortality in a specialist hospital in Gusau, Zamfara, North-Western Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis. 2017;28:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review of neonatal morbidity and mortality in Aminu Kano teaching hospital, Northern Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2007;37:130-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childhood mortality in children emergency Centre of Lagos university teaching hospital. Niger J Paediatr. 2011;38:131-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The trend of newborn morbidity and mortality in Benin City In: Abstract in Paediatric Association of Nigeria 32nd Annual Conference. 2001.

- [Google Scholar]

- An analysis of neonatal morbidity and mortality in Azare NorthEastern Nigeria. J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:25-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Retrospective assessment of neonatal morbidity and mortality in the special care baby unit of a private health facility in Benue state, North Central Nigeria. Niger J Paediatr. 2020;47:353-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity and mortality pattern of neonates admitted into nursery unit in Wad Medani hospital, Sudan. Sudan JMS. 2010;5:13-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neonatal morbidity and mortality in a rural tertiary hospital in Nigeria. CHRISMED J Health Res. 2018;5:8-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis and outcome of admission to the special care baby unit of Ahmadu Bello University teaching hospital, Zaria. Niger J Med. 1996;1:70-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- A 4 year review of neonatal outcome at the university of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13:321-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity and mortality patterns of admissions into the special care baby unit of university of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Gwagwalada, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12:389-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- A two-year review of outcome of neonatal admissions at the children emergency room of the Lagos state university teaching hospital, Ikeja Lagos, Paediatrics association of Nigeria scientific conference abstracts proceedings 2016. Niger J Paediatr. 2016;43:110-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neonatal deaths in North East Nigeria: 15 years of tale from a tertiary hospital, Paediatrics association of Nigeria scientific conference abstracts proceedings 2018. Niger J Paediatr. 2018;45:31-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity and mortality pattern among in-patients in the paediatric department of Olabisi Onabanjo University teaching hospital Sagamu over a twelve-month period In: Paper Presented at Scientific Conference of Paediatric Association of Nigeria in Enugu. 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity profile and outcome of newborns admitted into the neonatal unit of a secondary healthcare Centre in Benin City. Paediatrics Association of Nigeria scientific conference abstracts proceedings 2016. Niger J Paediatr. 2016;43:111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discharge against medical advice amongst neonates admitted into a special care baby unit in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Int J Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;40:12-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]